By Loulou Callister-Baker

Artists: Deanna Dowling, Tomas Richards, Cobi Taylor, Robyn Jordann

Blue Oyster Art Project Space (and Dutybound on Crawford St and outside both spaces)

Wednesday 5 - Saturday 29 August 2015

A Tragic Delusion decentralises the Blue Oyster space on Dowling Street by having the work of four emergent artists displayed inside the gallery, on the street and in another huge space above Dutybound, a quiet, unassuming book binder on Crawford Street. I have focused on the works in the show by Wellington artists, Deanna Dowling and Tomas Richards.

Gallery spaces provide and exist as a result of delusions. They harbour the delusions of artists – the people who endeavour to create, remix or distort our physical and conscious realities in a celebration of delusion. Galleries also hold an undertone of tragedy too - exhibiting has become vastly different to the practices of a handful of New Zealand spaces throughout the 80s and 90s, which were artist run, passionately independent, fighting all constraints of the system. In her two part text for the show, A Tragic Delusion, Director Chloe Geoghegan describes her own sense of tragic delusion “as a curator working within and supporting an aspirational white project space,” confined by current white-wall processes. But the question remains, does this ambitious show, which aims to “unearth, pick apart and situate what emergent sculpture, installation and performance is today”, achieve its goals or perpetuate further delusion?

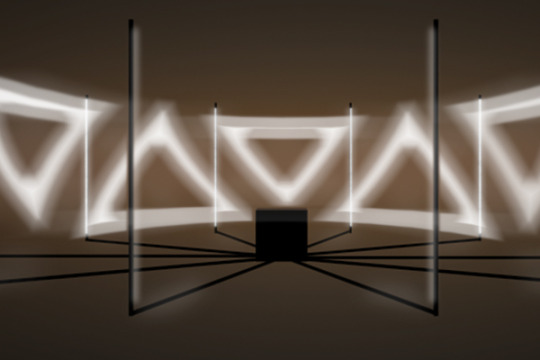

A long, narrow floorboard, once part of the Blue Oyster’s stable flooring arrangement, has disappeared and re-emerged at Dutybound in a subverted, sculptural state. Standing over the rectangle hole that forms a part of Tomas Richards’s work, Traversing Particles, one can see the littered earth beneath the gallery. This unclothing of the white project space feels somewhat of a reveal. The gallery can be deconstructed.

People, when describing lost love, often cite that you only know what you have when it’s gone – in a similar sense, the floorboard’s absence was briefly (surprisingly) felt. However, when I found the floorboard towering above me, with one of its ends leant against the rafters at Dutybound, I experienced another revelation. Rather than questioning and lamenting a loss, this was a celebration. Richards has made two significant works centred around one delightfully tactful move – by the removal of one thing we acknowledge its absence (and the meaning of the space around it) and by its arrangement in a new space, we can understand its sculptural potential. This is echoed further in the other miscellaneous objects like pin boards, a key cabinet, dust and dirt that Richards has moved from one place to the other. At the Dutybound space, Richards also has recordings of sounds, like traffic and machine gun fire that signals a green man, which can be heard when moving between the two spaces. This sound art is not just a thoughtful addition; it is a strong twine that ties the goals of this show together.

Deanna Dowling’s work also has a sense of discovery and subtlety, which quietly holds its own whilst also engaging in an open conversation with Richards’ work. Like Richards, Dowling’s work traverses beyond Blue Oyster’s physical boundaries. Presented almost as a montage of clues, Dowling’s video piece at the gallery provides hints of the materials and sounds that literally make up the building blocks of the world around us. Among the often still, sometimes silent shots that make up the five minute work are images of fine gold fillings, and piles of Oamaru stone in a quarry, which fade into a long take of the Phoenix House building in Dunedin (the recorded traffic sounds creating a sonic link to Richards’s recordings). The subjects of Dowling’s film faded in and out of my mind as I made my way between the Blue Oyster and Dutybound with a new, ebbing awareness for the material world around me.

Dowling’s In search of gold, the stone was there all along also includes two thrilling street art works. The first, a tiny crack in the pavement that the artist had filled with gold and Oamaru stone, was pointed out to me by the gallery assistant. However, I was alone in my search for the one outside Dutybound. While the gallery map has a “3” floating around where the work should be, I did not find it straight away. I saw bottle caps, broken glass among sidewalk tussocks and many unfilled cracks before I came across Dowling’s work. I may have looked strange with my head down walking around in tight circles, but this search lead to a string of meaningful observations. It revealed the subtle presence of urban decay in Dunedin, how an active seeking creates a feeling of reward, and – for me – it suggested the exciting possibilities of how a city could be used for artistic endeavours that were far more effective and enigmatic than the giant, graffiti works which seem to be covering Dunedin’s surfaces with a new found zealousness.

A Tragic Delusion has been put together to “explore artist-run exhibition ideals that existed outside of the gallery system in the 70s, 80s and 90s” – ideals born from the freedom of running shows in a large variety of spaces, rather than limiting art to its exhibition on white walls. A Tragic Delusion appropriately provided me with the initial building blocks to establish an insight into the history of sculptural practices in New Zealand. These blocks came in the form of piled Oamaru stones, of displaced floorboards and gallery office pin boards. Now these too are the symbols of tragic and celebratory delusion.

Image 1. Tomas Richards, 'Traversing Particles', 2015 (source: Blue Oyster Gallery)

Image 2. Tomas Richards, 'Traversing Particles', 2015 (source: Blue Oyster Gallery)

Image 3. Deanna Dowling, ‘In search of gold, the stone was there all along’ (film still), 2015 (source: Blue Oyster Gallery)

Image 3. Deanna Dowling, ‘In search of gold, the stone was there all along’ (detail), 2015 (source: Blue Oyster Gallery)

Image 4. Deanna Dowling, ‘In search of gold, the stone was there all along’, 2015 (source: Blue Oyster Gallery)